How powerful industries use regulatory agencies to protect their oligopolies

at the expense of competition and public interest.

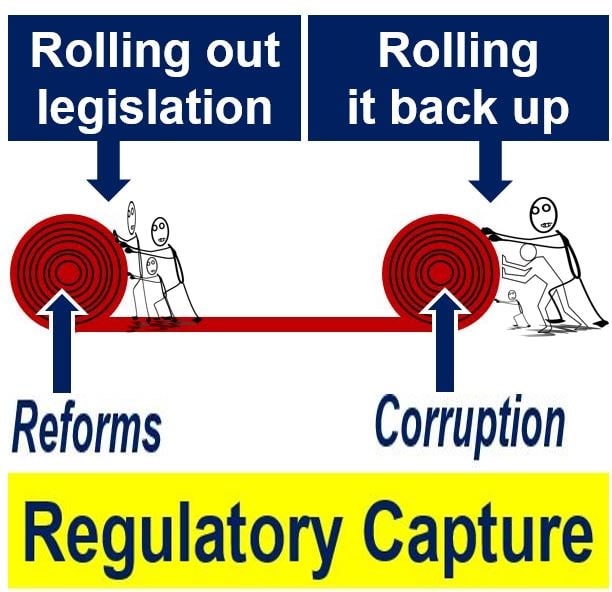

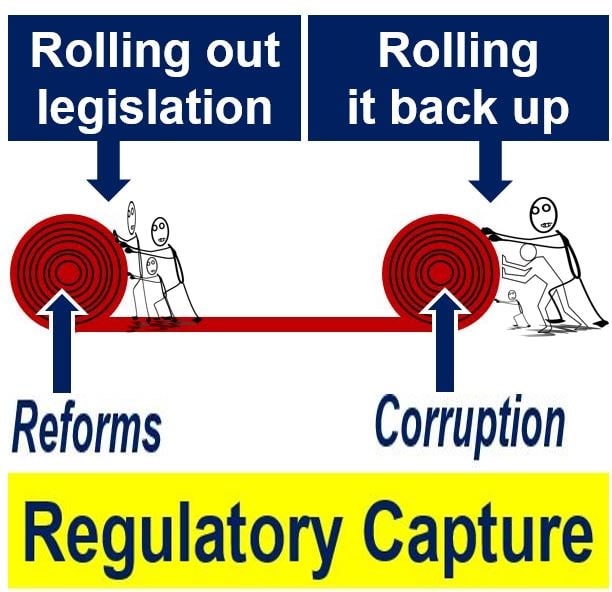

What is Regulatory Capture?

The Regulatory Capture categories TAP is highlighting are “Big Pharma, Vaccines, COVID-19,” “Medical Freedom and Natural Health,” “Big Energy,” “Federal Communications Commission (FCC),” “Department of Agriculture (DOA),” “Department of Defense (DOD),” and the “Department of Justice (DOJ).”

The Brookings Institution is a prestigious Washington research organization. In the following article about the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) written in 2011, Brookings Senior Fellow Daniel Kaufmann and Veronika Penciakova wrote about a case in which a federal judge rejected a settlement negotiated by the SEC assessing a $385 million fine against Citibank. It was unusual for a court to reject a settlement agreed to by the SEC. The bank had been charged with negligence related to its misleading sale of toxic mortgage-backed securities, which ultimately cost investors nearly $700 million but earned the bank a handsome profit of almost $160 million.

The court decision gave the authors an opportunity to write about the problem of “regulatory capture,” focusing chiefly on the SEC, but in a way that made it clear that the “problem” was hardly limited to that one agency. They describe it as “a form of corruption” and then let the numbers speak for themselves.

“SEC v. Citigroup can be seen in the context of the intimate relationship between the agency and the powerful banks it regulates, one which has prevailed for years and weakened the regulatory power of the SEC. The financial crisis and subsequent call for reform provided ample opportunity to tackle such undue influence and regulatory capture, which occurs when the regulator is unduly influenced by the interests of regulated entities.”

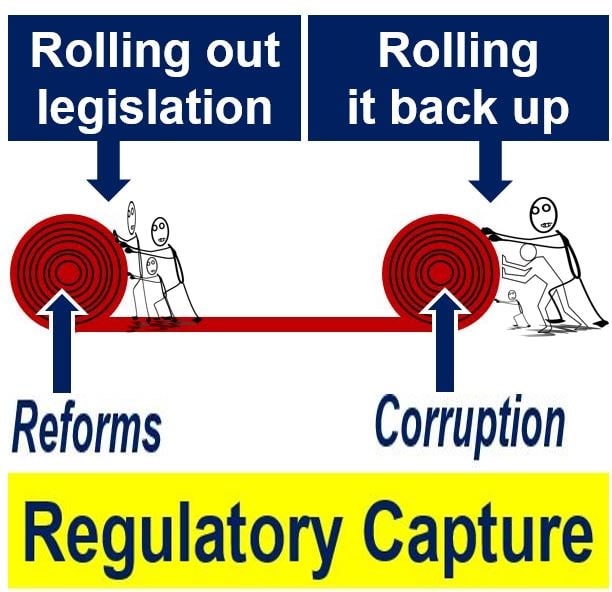

“At the beginning of the new administration and during the early stages of the Dodd-Frank reform bill preparation, a rebalancing of power between the weakened regulator and powerful financial institutions was expected.”

“Yet, once the bill was adopted reality began to sink in. The reform bill failed to directly address the problem of banks that were too big to fail, and left crucial implementation matters to the discretion of weak regulatory agencies such as the SEC. It seemed that power shifted back from Washington to Wall Street again.”

“The SEC has a history of regulatory capture”

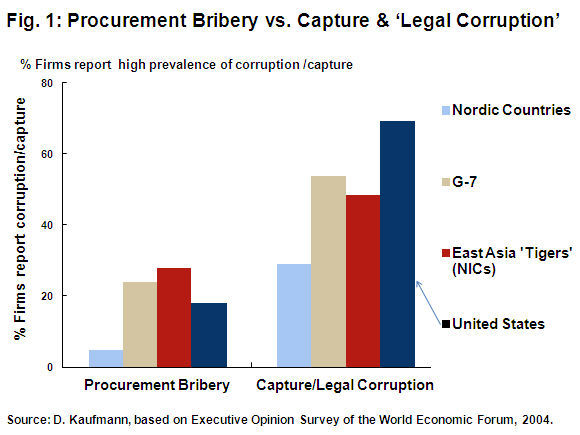

“Whether covert or overt, elements of regulatory capture have been evident for some time. In the decade leading up to the financial crisis, deregulation in the U.S. financial sector weakened regulatory agencies. More generally, seven years ago I codified the extent of “state capture” and “legal corruption” through a survey of enterprises in over 100 countries.”

“The extent of capture afflicting the U.S. was very high; it not only rated well below other industrialized countries, but found itself among the bottom half worldwide (figure 1).

…Furthermore, preceding the financial crisis, the SEC became aware that Bernard Madoff, who had served on the commission’s advisory committee and had been previously reported for securities violations, was mismanaging his customers’ funds in the tens of billions of dollars.”

“Yet the agency failed to probe deeper and unmask his Ponzi scheme. The SEC also neglected to take action against financier R. Allen Stanford, who swindled investors out of $8 billion, although allegations of fraud and possible money laundering had been levied against him in the past.”

“Expectations of change were not realized”

“The onset of the financial crisis revealed the weakness of the financial sector and the extent to which regulators had been captured. It spurred public outrage and calls for change.”

“When the new administration entered office it brought with it a clear appreciation for the problem of capture. As early as 2007, then Senator Obama, during a major address at Nasdaq in New York City, recognized that “turning a blind eye to cronyism in our midst put us all in jeopardy” and that “we [were] going to have to adapt our institutions to a new world.”

“Over three years later, regulatory reforms were adopted through the Dodd-Frank bill, which, at least on paper, signaled a move in the right direction toward stronger regulations and the potential for somewhat reduced capture. Yet, recent events are exposing weaknesses in Dodd-Frank. The bill failed to address crucial implementation details and was vague in some regulatory matters, leaving discretion in the hands of weak regulators. Since the mid-term congressional elections last year, lobbyists for large financial institutions and their allies in Congress have been working hard to keep, as intact as possible, the deregulated status quo that prevailed prior to the financial crisis.”…

“Regulatory capture of the SEC today impacts enforcement”

“The close ties between banks and the SEC are symptomatic of the sector’s influence over the regulator.” A study by the Project on Government Oversight found that in the past five years, 219 former SEC employees filed nearly 800 disclosure statements for representing their clients’ dealings with the agency, and of these, about half (403) were filed by people who worked for the SEC’s enforcement division. Even the regulator’s top enforcement official has moved back and forth between the Justice Department, Deutsche Bank, and the SEC.

“Such close ties may ultimately affect enforcement. An internal investigation found that a former SEC official blocked the agency’s investigation of R. Allen Stanford for nearly seven years, and then went on to work for him. More recently, the SEC’s head enforcement official was investigated (but cleared) after Citigroup hired his former boss to participate in its defense against charges unrelated to the case before Judge Rakoff. Negotiations between the parties resulted in the charges against two executives being reduced. In an open investigation, the SEC’s inspector general is looking into allegations that the frequent hiring of former SEC attorneys by a particular firm has contributed to the agency’s failure to take appropriate actions against it.”

“One impact of such capture has been weak enforcement. While the SEC can take companies to court, extract civil penalties and bring contempt charges for repeat violations, the agency has only given ‘slaps on the wrist’ to those firms involved in the financial crisis. Instead, it has preferred to settle out of court with big banks. These settlements allow banks to merely pledge to desist from breaching antifraud laws again and pay penalties—which are typically not very onerous considering the bank’s breach and benefits they derived—without ever having to admit to any wrongdoing.”

“…Furthermore, the SEC has shied away from closely monitoring the banks’ compliance progress, and has done little to impose high penalties for failure to comply with pledges made….

…A New York Times analysis found that over the past 15 years, at least 51 cases have involved recidivism by 19 Wall Street firms. In many of these cases, the SEC could bring contempt of court charges, but it has not done so in at least 10 years. Most major banks are repeat violators. Bank of America, for instance, has four violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and four for purposeful fraud by securities firms since 1998. During the same period, Citigroup amassed five violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and three violations for purposeful fraud by securities firms. None of these past cases were even mentioned in the SEC’s charges against Citigroup in the case before Judge Rakoff, and no contempt of court charges have been made against the bank.”

Read the full article here: “Judge Rakoff Challenge to the S.E.C.: Can Regulatory Capture be Reversed?”

Source: Brookings

Clearly, regulatory capture is not limited to the SEC. The term directly applies to the Justice Department as well, as DOJ is the department that prosecutes criminal charges against financial institutions—the SEC only handles civil cases involving fines. But the causes and the scale of regulatory capture obviously extend to other branches of government. One must ask, “To what branches of government do they not extend?”

The case of the SEC reveals how regulatory capture works in other industries and agencies as well. The appointment of top officials and lawyers for all agencies is filtered through a political process involving prior commitments made by presidential candidates and congressional candidates who take seats on legislative committees overseeing the agencies. The power of money in politics creates “the best government money can buy.”

Over time, we will publish articles laying bare the consequences of regulatory capture in all of the agencies named below.

Regulatory Capture Categories

How powerful industries use regulatory agencies to protect their oligopolies at the expense of competition and public interest.

What is Regulatory Capture?

The Regulatory Capture categories TAP is highlighting are “Big Pharma, Vaccines, COVID-19,” “Medical Freedom and Natural Health,” “Big Energy,” “Federal Communications Commission (FCC),” “Department of Agriculture (DOA),” “Department of Defense (DOD),” and the “Department of Justice (DOJ).”

Links to these categories can be found at the bottom of this page.

The Brookings Institution is a prestigious Washington research organization. In the following article about the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) written in 2011, Brookings Senior Fellow Daniel Kaufmann and Veronika Penciakova wrote about a case in which a federal judge rejected a settlement negotiated by the SEC assessing a $385 million fine against Citibank. It was unusual for a court to reject a settlement agreed to by the SEC. The bank had been charged with negligence related to its misleading sale of toxic mortgage-backed securities, which ultimately cost investors nearly $700 million but earned the bank a handsome profit of almost $160 million.

The court decision gave the authors an opportunity to write about the problem of “regulatory capture,” focusing chiefly on the SEC, but in a way that made it clear that the “problem” was hardly limited to that one agency. They describe it as “a form of corruption” and then let the numbers speak for themselves.

“SEC v. Citigroup can be seen in the context of the intimate relationship between the agency and the powerful banks it regulates, one which has prevailed for years and weakened the regulatory power of the SEC.

The financial crisis and subsequent call for reform provided ample opportunity to tackle such undue influence and regulatory capture, which occurs when the regulator is unduly influenced by the interests of regulated entities.”

“At the beginning of the new administration and during the early stages of the Dodd-Frank reform bill preparation, a rebalancing of power between the weakened regulator and powerful financial institutions was expected.”

“Yet, once the bill was adopted reality began to sink in. The reform bill failed to directly address the problem of banks that were too big to fail, and left crucial implementation matters to the discretion of weak regulatory agencies such as the SEC. It seemed that power shifted back from Washington to Wall Street again.”

“The SEC has a history of regulatory capture”

“Whether covert or overt, elements of regulatory capture have been evident for some time. In the decade leading up to the financial crisis, deregulation in the U.S. financial sector weakened regulatory agencies. More generally, seven years ago I codified the extent of “state capture” and “legal corruption” through a survey of enterprises in over 100 countries.”

“The extent of capture afflicting the U.S. was very high; it not only rated well below other industrialized countries, but found itself among the bottom half worldwide (figure 1).

…Furthermore, preceding the financial crisis, the SEC became aware that Bernard Madoff, who had served on the commission’s advisory committee and had been previously reported for securities violations, was mismanaging his customers’ funds in the tens of billions of dollars.”

“Yet the agency failed to probe deeper and unmask his Ponzi scheme. The SEC also neglected to take action against financier R. Allen Stanford, who swindled investors out of $8 billion, although allegations of fraud and possible money laundering had been levied against him in the past.”

“Expectations of change were not realized”

“The onset of the financial crisis revealed the weakness of the financial sector and the extent to which regulators had been captured. It spurred public outrage and calls for change.”

“When the new administration entered office it brought with it a clear appreciation for the problem of capture. As early as 2007, then Senator Obama, during a major address at Nasdaq in New York City, recognized that “turning a blind eye to cronyism in our midst put us all in jeopardy” and that “we [were] going to have to adapt our institutions to a new world.”

“Over three years later, regulatory reforms were adopted through the Dodd-Frank bill, which, at least on paper, signaled a move in the right direction toward stronger regulations and the potential for somewhat reduced capture. Yet, recent events are exposing weaknesses in Dodd-Frank. The bill failed to address crucial implementation details and was vague in some regulatory matters, leaving discretion in the hands of weak regulators. Since the mid-term congressional elections last year, lobbyists for large financial institutions and their allies in Congress have been working hard to keep, as intact as possible, the deregulated status quo that prevailed prior to the financial crisis.”…

“Regulatory capture of the SEC today impacts enforcement”

“The close ties between banks and the SEC are symptomatic of the sector’s influence over the regulator.” A study by the Project on Government Oversight found that in the past five years, 219 former SEC employees filed nearly 800 disclosure statements for representing their clients’ dealings with the agency, and of these, about half (403) were filed by people who worked for the SEC’s enforcement division. Even the regulator’s top enforcement official has moved back and forth between the Justice Department, Deutsche Bank, and the SEC.

“Such close ties may ultimately affect enforcement. An internal investigation found that a former SEC official blocked the agency’s investigation of R. Allen Stanford for nearly seven years, and then went on to work for him. More recently, the SEC’s head enforcement official was investigated (but cleared) after Citigroup hired his former boss to participate in its defense against charges unrelated to the case before Judge Rakoff. Negotiations between the parties resulted in the charges against two executives being reduced. In an open investigation, the SEC’s inspector general is looking into allegations that the frequent hiring of former SEC attorneys by a particular firm has contributed to the agency’s failure to take appropriate actions against it.”

“One impact of such capture has been weak enforcement. While the SEC can take companies to court, extract civil penalties and bring contempt charges for repeat violations, the agency has only given ‘slaps on the wrist’ to those firms involved in the financial crisis.

Instead, it has preferred to settle out of court with big banks. These settlements allow banks to merely pledge to desist from breaching antifraud laws again and pay penalties—which are typically not very onerous considering the bank’s breach and benefits they derived—without ever having to admit to any wrongdoing.”

“…Furthermore, the SEC has shied away from closely monitoring the banks’ compliance progress, and has done little to impose high penalties for failure to comply with pledges made….

…A New York Times analysis found that over the past 15 years, at least 51 cases have involved recidivism by 19 Wall Street firms. In many of these cases, the SEC could bring contempt of court charges, but it has not done so in at least 10 years. Most major banks are repeat violators. Bank of America, for instance, has four violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and four for purposeful fraud by securities firms since 1998. During the same period, Citigroup amassed five violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and three violations for purposeful fraud by securities firms. None of these past cases were even mentioned in the SEC’s charges against Citigroup in the case before Judge Rakoff, and no contempt of court charges have been made against the bank.”

Read the full article here: “Judge Rakoff Challenge to the S.E.C.: Can Regulatory Capture be Reversed?”

Source: Brookings

Clearly, regulatory capture is not limited to the SEC. The term directly applies to the Justice Department as well, as DOJ is the department that prosecutes criminal charges against financial institutions—the SEC only handles civil cases involving fines. But the causes and the scale of regulatory capture obviously extend to other branches of government. One must ask, “To what branches of government do they not extend?”

The case of the SEC reveals how regulatory capture works in other industries and agencies as well. The appointment of top officials and lawyers for all agencies is filtered through a political process involving prior commitments made by presidential candidates and congressional candidates who take seats on legislative committees overseeing the agencies. The power of money in politics creates “the best government money can buy.”

Over time, we will publish articles laying bare the consequences of regulatory capture in all of the agencies named below.

Regulatory Capture Categories

Regulatory Capture

How powerful industries use regulatory agencies to protect their oligopolies at the expense of competition and public interest.

What is Regulatory Capture?

The Regulatory Capture categories TAP is highlighting are “Big Pharma, Vaccines, COVID-19,” “Medical Freedom and Natural Health,” “Big Energy,” “Federal Communications Commission (FCC),” “Department of Agriculture (DOA),” “Department of Defense (DOD),” and the “Department of Justice (DOJ).”

Links to these categories can be found

at the bottom of this page.

The Brookings Institution is a prestigious Washington research organization. In the following article about the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) written in 2011, Brookings Senior Fellow Daniel Kaufmann and Veronika Penciakova wrote about a case in which a federal judge rejected a settlement negotiated by the SEC assessing a $385 million fine against Citibank. It was unusual for a court to reject a settlement agreed to by the SEC. The bank had been charged with negligence related to its misleading sale of toxic mortgage-backed securities, which ultimately cost investors nearly $700 million but earned the bank a handsome profit of almost $160 million.

The court decision gave the authors an opportunity to write about the problem of “regulatory capture,” focusing chiefly on the SEC, but in a way that made it clear that the “problem” was hardly limited to that one agency. They describe it as “a form of corruption” and then let the numbers speak for themselves.

“SEC v. Citigroup can be seen in the context of the intimate relationship between the agency and the powerful banks it regulates, one which has prevailed for years and weakened the regulatory power of the SEC. The financial crisis and subsequent call for reform provided ample opportunity to tackle such undue influence and regulatory capture, which occurs when the regulator is unduly influenced by the interests of regulated entities.”

“At the beginning of the new administration and during the early stages of the Dodd-Frank reform bill preparation, a rebalancing of power between the weakened regulator and powerful financial institutions was expected.”

“Yet, once the bill was adopted reality began to sink in. The reform bill failed to directly address the problem of banks that were too big to fail, and left crucial implementation matters to the discretion of weak regulatory agencies such as the SEC. It seemed that power shifted back from Washington to Wall Street again.”

Shifting Back to Wall Street?"

“The SEC has a history of regulatory capture”

“Whether covert or overt, elements of regulatory capture have been evident for some time. In the decade leading up to the financial crisis, deregulation in the U.S. financial sector weakened regulatory agencies. More generally, seven years ago I codified the extent of “state capture” and “legal corruption” through a survey of enterprises in over 100 countries.”

“The extent of capture afflicting the U.S. was very high; it not only rated well below other industrialized countries, but found itself among the bottom half worldwide (figure 1).

“Yet the agency failed to probe deeper and unmask his Ponzi scheme. The SEC also neglected to take action against financier R. Allen Stanford, who swindled investors out of $8 billion, although allegations of fraud and possible money laundering had been levied against him in the past.”

“Expectations of change were not realized”

“The onset of the financial crisis revealed the weakness of the financial sector and the extent to which regulators had been captured. It spurred public outrage and calls for change.”

“When the new administration entered office it brought with it a clear appreciation for the problem of capture. As early as 2007, then Senator Obama, during a major address at Nasdaq in New York City, recognized that “turning a blind eye to cronyism in our midst put us all in jeopardy” and that “we [were] going to have to adapt our institutions to a new world.”

“Over three years later, regulatory reforms were adopted through the Dodd-Frank bill, which, at least on paper, signaled a move in the right direction toward stronger regulations and the potential for somewhat reduced capture. Yet, recent events are exposing weaknesses in Dodd-Frank. The bill failed to address crucial implementation details and was vague in some regulatory matters, leaving discretion in the hands of weak regulators. Since the mid-term congressional elections last year, lobbyists for large financial institutions and their allies in Congress have been working hard to keep, as intact as possible, the deregulated status quo that prevailed prior to the financial crisis.”…

“Regulatory capture of the SEC today

impacts enforcement”

“The close ties between banks and the SEC are symptomatic of the sector’s influence over the regulator.” A study by the Project on Government Oversight found that in the past five years, 219 former SEC employees filed nearly 800 disclosure statements for representing their clients’ dealings with the agency, and of these, about half (403) were filed by people who worked for the SEC’s enforcement division. Even the regulator’s top enforcement official has moved back and forth between the Justice Department, Deutsche Bank, and the SEC.

“Such close ties may ultimately affect enforcement. An internal investigation found that a former SEC official blocked the agency’s investigation of R. Allen Stanford for nearly seven years, and then went on to work for him. More recently, the SEC’s head enforcement official was investigated (but cleared) after Citigroup hired his former boss to participate in its defense against charges unrelated to the case before Judge Rakoff. Negotiations between the parties resulted in the charges against two executives being reduced. In an open investigation, the SEC’s inspector general is looking into allegations that the frequent hiring of former SEC attorneys by a particular firm has contributed to the agency’s failure to take appropriate actions against it.”

“One impact of such capture has been weak enforcement. While the SEC can take companies to court, extract civil penalties and bring contempt charges for repeat violations, the agency has only given ‘slaps on the wrist’ to those firms involved in the financial crisis. Instead, it has preferred to settle out of court with big banks. These settlements allow banks to merely pledge to desist from breaching antifraud laws again and pay penalties—which are typically not very onerous considering the bank’s breach and benefits they derived—without ever having to admit to any wrongdoing.”

“…Furthermore, the SEC has shied away from closely monitoring the banks’ compliance progress, and has done little to impose high penalties for failure to comply with pledges made….

…A New York Times analysis found that over the past 15 years, at least 51 cases have involved recidivism by 19 Wall Street firms. In many of these cases, the SEC could bring contempt of court charges, but it has not done so in at least 10 years. Most major banks are repeat violators. Bank of America, for instance, has four violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and four for purposeful fraud by securities firms since 1998. During the same period, Citigroup amassed five violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and three violations for purposeful fraud by securities firms. None of these past cases were even mentioned in the SEC’s charges against Citigroup in the case before Judge Rakoff, and no contempt of court charges have been made against the bank.”

Read the full article here: “Judge Rakoff Challenge to the S.E.C.:

Can Regulatory Capture be Reversed?”

Source: Brookings

Clearly, regulatory capture is not limited to the SEC. The term directly applies to the Justice Department as well, as DOJ is the department that prosecutes criminal charges against financial institutions—the SEC only handles civil cases involving fines. But the causes and the scale of regulatory capture obviously extend to other branches of government. One must ask, “To what branches of government do they not extend?”

The case of the SEC reveals how regulatory capture works in other industries and agencies as well. The appointment of top officials and lawyers for all agencies is filtered through a political process involving prior commitments made by presidential candidates and congressional candidates who take seats on legislative committees overseeing the agencies. The power of money in politics creates “the best government money can buy.”

Over time, we will publish articles laying bare the consequences of regulatory capture in all of the agencies named below.

Regulatory Capture Categories