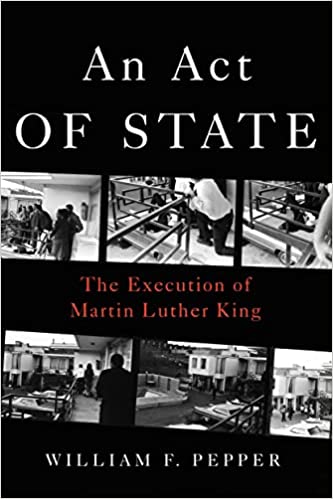

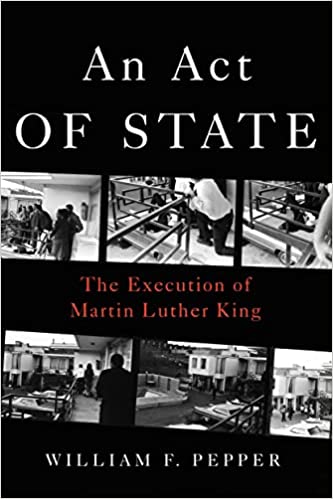

An Act of State

The Execution of Martin Luther King

By William F. Pepper

A Book Review by Chuck Fall

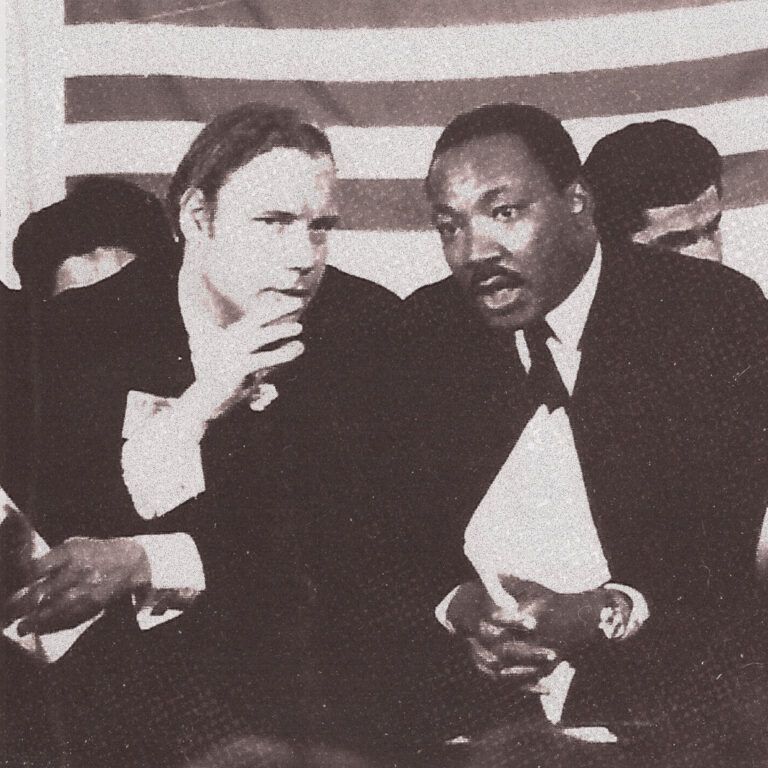

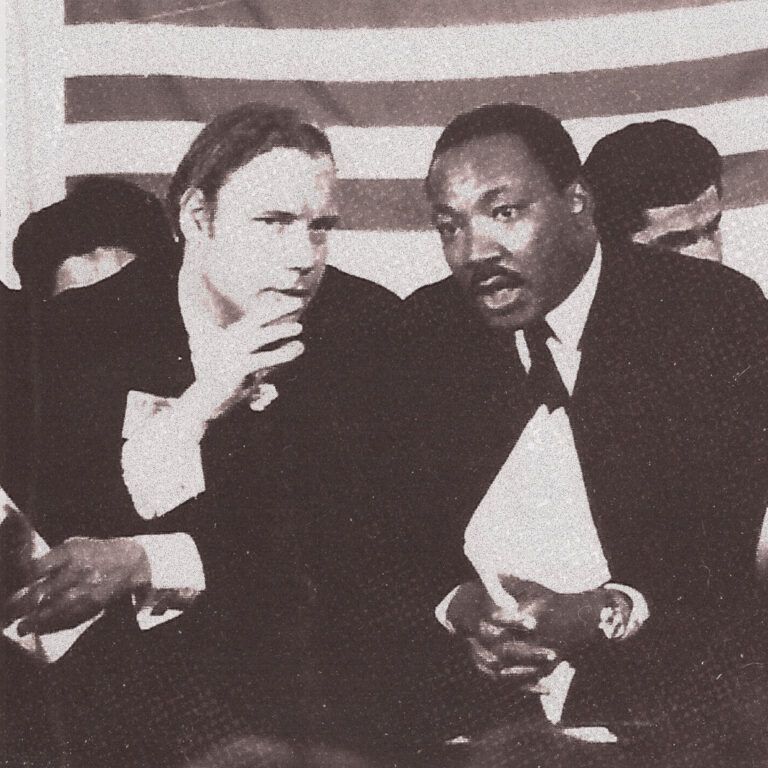

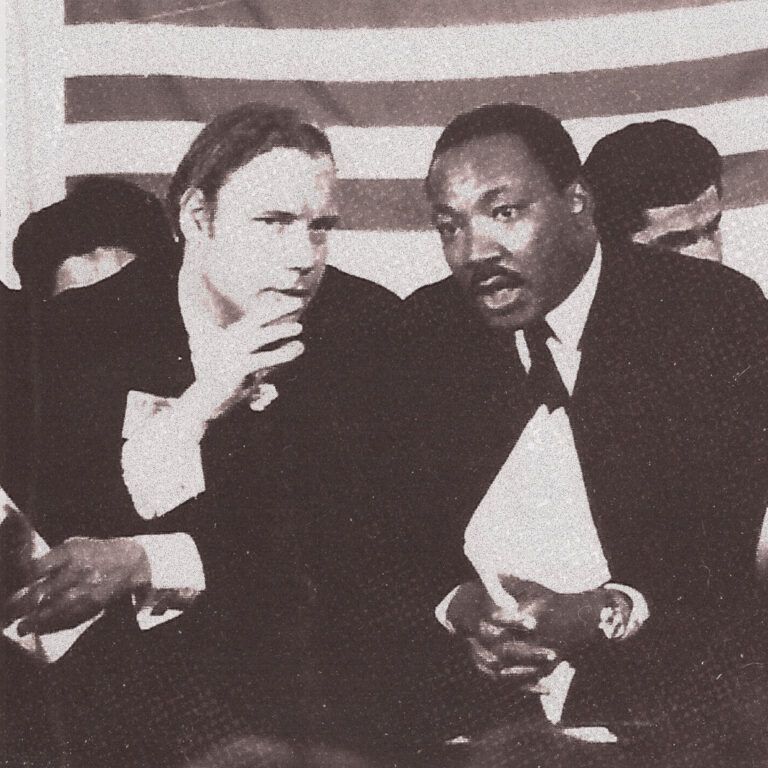

William Pepper befriended Martin Luther King after King read a Ramparts Magazine article in 1967 about atrocities in the Vietnam War. Pepper’s report moved Dr. King to take a more critical stance against the war and later led him to call for a Poor People’s Movement, fusing two currents at a time of revolutionary change.

In An Act of State, William Pepper, a radical human rights lawyer, tells the story of engaging with the King family to uncover the truth around King’s murder.

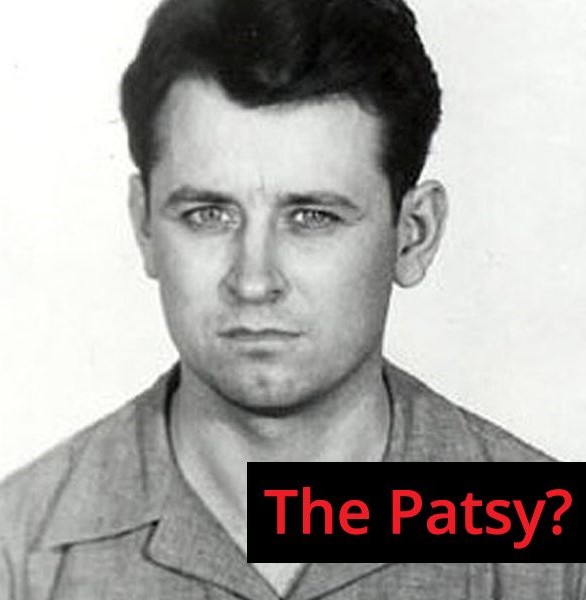

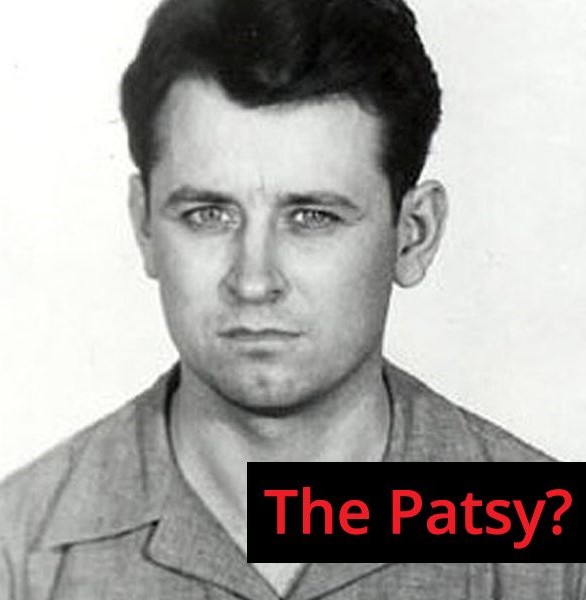

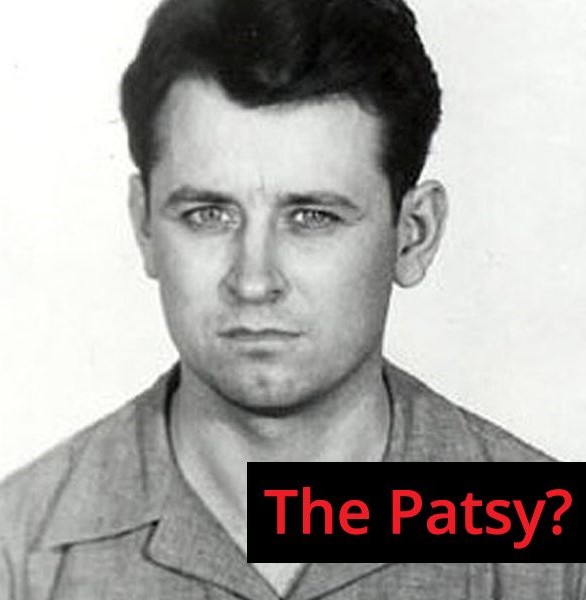

MLK’s assassination was a profound shock to Pepper, which at the time drove him away from public activism to professional work, but he would return to the crime scene, almost 12 years later, on behalf of the King family to try to get James Earl Ray a new trial.

Within three days of his guilty plea, Ray claimed his innocence; Pepper’s investigation contends that Ray was set up as a scapegoat to support the state’s case of a lone gunman assassin; however, Pepper’s counter narrative contends that there was a conspiracy and it was an act of state, which describes the thesis of King’s assassination. To exonerate Ray, Pepper needed to convince a jury of an alternative explanation for what happened.

As a way to build public interest for a new trial for Ray, Pepper conducted a mock trial of the King assassination on BBC television. Though Pepper was never able to secure a new trial for Ray, who died in jail in 1998, the King family did sue Lloyd Jowers, who implicated himself as a result of the BBC TV production.

Lloyd Jowers was mentioned as a suspect, given that witnesses saw him handle a rifle reportedly used in the crime. Jowers was the landlord for the short-term room rental from which Ray is alleged to have shot King.

To deflect his role as the actual assassin, Lloyd Jowers went on ABC and told Sam Donaldson that he participated in the assassination and knew who the assassin was.

The King family sued Lloyd Jowers, and through the case, Pepper demonstrated by a preponderance of evidence that Ray did not kill King and that more plausibly it was a conspiracy of local and federal law enforcement. They won a $100.00 financial award from Jowers, and the King family was satisfied with the revelation of a conspiracy.

In Pepper’s account, there were a lot of people involved in the assassination: local mafia, local police, the FBI, and military intelligence and assassin teams that would be used as a backup if the primary assassin team of local people failed; it’s complicated.

The Plot to Kill King and Orders to Kill are two other titles by William Pepper about the King assassination that provide credible and plausible explanations for what happened and why it happened.

In a nutshell, Ray was framed and an elaborate plot was engineered; there were insiders in the Civil Rights Movement who are alleged to have aided and abetted the assassination, and there has been an ongoing cover-up that involves misinformation and assassination. Pepper reports a fascinating story of deceit and intrigue as he pieces together the bits and shards of evidence, much of it secondhand.

From his days in the 1950s and early 1960s, Pepper tells the story of King’s maturation as a social and political activist. It was a great triumph for the movement when President Johnson signed into law in 1965 the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. But King kept moving forward and wanted more reforms.

In 1967, King delivered his famous speech condemning the Vietnam War, and it was a shot across the bow for the establishment. King exhibited a willingness to branch out from civil and voting rights to more radical and contentious issues like opposing war (the military industrial complex) and opposing the systemic impoverishment of people of color. Some in the movement thought King betrayed a tacit agreement to not get too “uppity” and to not ask for too much, like ending a war.

When I think about the 1960s assassinations, including those of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Robert F. Kennedy, I wonder how history would have unfolded if these great leaders had not been killed. It is easy to imagine that the geopolitical affairs of an imperial American power would have been brought to heel under an anti-militarism policy and a pro-social justice movement. This was certainly King’s destiny.

Indeed, it is possible to imagine that if the four assassinated leaders had lived a full life, that great arc of a just history that King confidently believed was available to humankind might have unfolded.

Perhaps the highlight of An Act of State is Chapter 10, which is a discussion of King’s philosophy about change, where he was willing to go, and the implications of this for his fate. However, it should inform our current thinking about where we should be as a movement and the stance we must take to effect change: King’s vision.

Pepper eloquently recites King’s philosophy of anti-materialism and a deep humanism that would oppose the relentless drive into a consumeristic, materialistic society that would prove antagonistic to the basic principles of dignity for all and the pursuit of a just society.

To highlight some of the text from Chapter 10: A Vision unto Death, a Truth Beyond the Grave, Pepper observes: King, he says, “inherited a dehumanized society… where all values are reduced to market values and market prices… King confronted societies’ “insatiable quest for money and material consumption.” “As the growth of corporate power parallels the increasing dominance of materialism, the movement for community control and localization becomes the natural reaction to the process of society’s dehumanization that Martin Luther King sought to reverse.”

“At the heart of the Poor People’s Campaign was the goal of empowering people in their communities to create a better life in balance with nature… and becoming part of the wooden world as zones of accountability and responsibility, which they manage themselves.”

King saw a problem in the “dominance of western materialism.” He saw the “insatiable quest for money…” and juxtaposed that with the “Poor People’s Campaign” as a “revolutionary undertaking” to counteract the pursuit of money with the pursuit of social justice.

King further challenged members of his own faith by calling Christianity “a religion of materialism” and criticizing it for undermining the world’s tribal people “across five continents, over five centuries, and enabling the Europeans to achieve world dominance of global resources.”

King scathingly denounces European culture as carrying the “materialistic torch” that “caused the deaths of hundreds of millions of people…”His critique of European culture saw it as a “materially advanced technological society running away from… Judeo-Christian heritage…” Pepper goes on to say that “the military industrial complex… [King saw it] as violating American cultural heritage by making the United States the world’s greatest purveyors of violence.””Poignantly, King prophesied that the growth of militarism would cause the end of democracy.

In King’s view, “the only alternative to disaster was to promote the perception of the oneness of humankind over the public policies of the nation.”

King aligned explicitly with Ghandi’s vision for change through civil disobedience, and he aligned with Ghandi’s humanitarian sensibility, which Pepper traces to a philosopher named John Ruskin, a critic living in the UK.

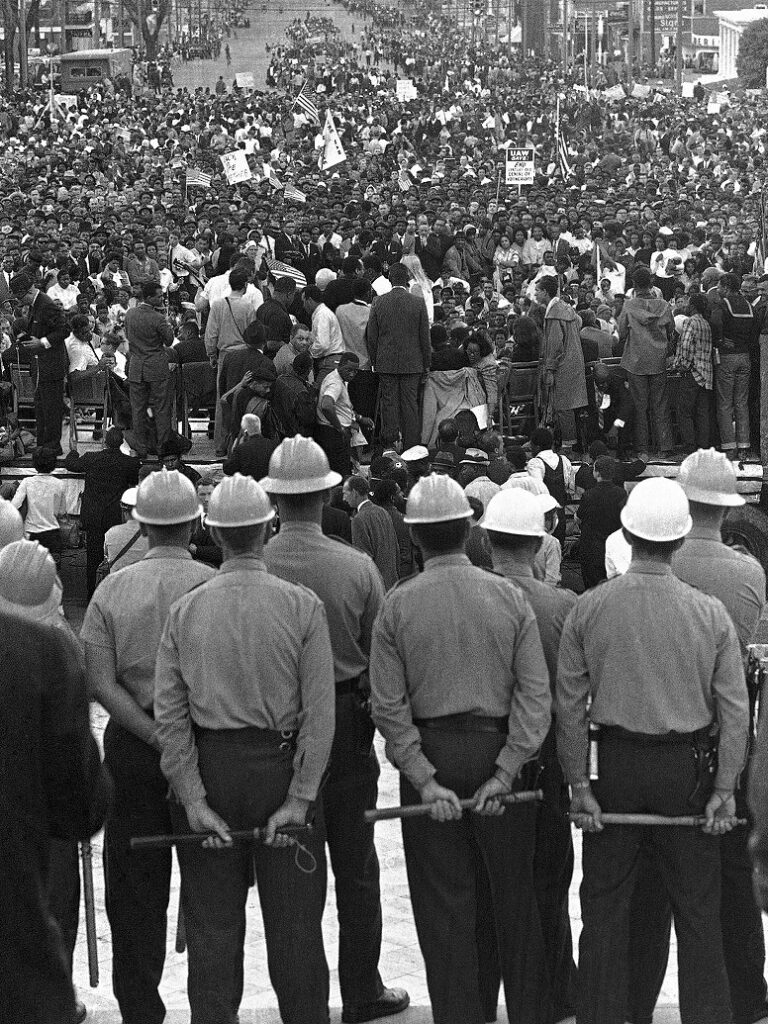

Pepper notes that by 1967, no national leader had emerged to lead the anti-war effort until MLK made his views known. As a warning to the establishment, a largely white demonstration involving 200,000 mostly middle-class protestors converged on the Pentagon, encircling it, and this presaged what would happen in Washington DC with a Poor People’s Campaign.

King was “attempting to confront the core issue of economic injustices running through American society… which included protesting the war in Vietnam and the growth of militarism.”

This “new struggle brought MLK into direct conflict with the Federal Government and its numerous agency surrogates… [serving] corporate interests.”

King’s movement, Pepper observes, was more “akin to a class revolution than an anti-colonial struggle,” and for this reason, King’s destiny was cut short by an “act of state.”

So, what are we, the readers, supposed to do with the knowledge that our government, or surrogates of our government, national security state agents, killed an American citizen endeavoring to affect a social revolution?

Well, for one, we should accept that the attack on King and others in the 1960s was a counter-revolution conducted by agents of the state; we need to accept that, in effect, historical possibilities were denied by the assassinations. Justice means reclaiming history, forcing accountability with truth commissions, and demanding reparations for the peace dividend we should have gotten.

We must then call for the same thing King did… a way to redeem King’s vision, to give King’s vision the same currency it had when he was killed, and to continue moving forward as a movement from where he left off…because since King’s assassination, things have only gotten worse in terms of our society descending into materialism and militarism. Society has degraded since King’s death. Let’s go back, figuratively speaking, and set things right.

Check out the link below for an interview with William Pepper that sheds light on the movement Dr. King was advancing in 1967:

https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/WFP020403.pdf

An Act of State

The Execution of Martin Luther King

By William F. Pepper

A Book Review by Chuck Fall

William Pepper befriended Martin Luther King after King read a Ramparts Magazine article in 1967 about atrocities in the Vietnam War. Pepper’s report moved Dr. King to take a more critical stance against the war and later led him to call for a Poor People’s Movement, fusing two currents at a time of revolutionary change.

In An Act of State, William Pepper, a radical human rights lawyer, tells the story of engaging with the King family to uncover the truth around King’s murder.

MLK’s assassination was a profound shock to Pepper, which at the time drove him away from public activism to professional work, but he would return to the crime scene, almost 12 years later, on behalf of the King family to try to get James Earl Ray a new trial.

Within three days of his guilty plea, Ray claimed his innocence; Pepper’s investigation contends that Ray was set up as a scapegoat to support the state’s case of a lone gunman assassin; however, Pepper’s counter narrative contends that there was a conspiracy and it was an act of state, which describes the thesis of King’s assassination. To exonerate Ray, Pepper needed to convince a jury of an alternative explanation for what happened.

As a way to build public interest for a new trial for Ray, Pepper conducted a mock trial of the King assassination on BBC television. Though Pepper was never able to secure a new trial for Ray, who died in jail in 1998, the King family did sue Lloyd Jowers, who implicated himself as a result of the BBC TV production.

Lloyd Jowers was mentioned as a suspect, given that witnesses saw him handle a rifle reportedly used in the crime. Jowers was the landlord for the short-term room rental from which Ray is alleged to have shot King.

To deflect his role as the actual assassin, Lloyd Jowers went on ABC and told Sam Donaldson that he participated in the assassination and knew who the assassin was.

The King family sued Lloyd Jowers, and through the case, Pepper demonstrated by a preponderance of evidence that Ray did not kill King and that more plausibly it was a conspiracy of local and federal law enforcement. They won a $100.00 financial award from Jowers, and the King family was satisfied with the revelation of a conspiracy.

In Pepper’s account, there were a lot of people involved in the assassination: local mafia, local police, the FBI, and military intelligence and assassin teams that would be used as a backup if the primary assassin team of local people failed; it’s complicated.

The Plot to Kill King and Orders to Kill are two other titles by William Pepper about the King assassination that provide credible and plausible explanations for what happened and why it happened.

In a nutshell, Ray was framed and an elaborate plot was engineered; there were insiders in the Civil Rights Movement who are alleged to have aided and abetted the assassination, and there has been an ongoing cover-up that involves misinformation and assassination. Pepper reports a fascinating story of deceit and intrigue as he pieces together the bits and shards of evidence, much of it secondhand.

From his days in the 1950s and early 1960s, Pepper tells the story of King’s maturation as a social and political activist. It was a great triumph for the movement when President Johnson signed into law in 1965 the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. But King kept moving forward and wanted more reforms.

In 1967, King delivered his famous speech condemning the Vietnam War, and it was a shot across the bow for the establishment. King exhibited a willingness to branch out from civil and voting rights to more radical and contentious issues like opposing war (the military industrial complex) and opposing the systemic impoverishment of people of color. Some in the movement thought King betrayed a tacit agreement to not get too “uppity” and to not ask for too much, like ending a war.

When I think about the 1960s assassinations, including those of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Robert F. Kennedy, I wonder how history would have unfolded if these great leaders had not been killed. It is easy to imagine that the geopolitical affairs of an imperial American power would have been brought to heel under an anti-militarism policy and a pro-social justice movement. This was certainly King’s destiny.

Indeed, it is possible to imagine that if the four assassinated leaders had lived a full life, that great arc of a just history that King confidently believed was available to humankind might have unfolded.

Perhaps the highlight of An Act of State is Chapter 10, which is a discussion of King’s philosophy about change, where he was willing to go, and the implications of this for his fate. However, it should inform our current thinking about where we should be as a movement and the stance we must take to effect change: King’s vision.

Pepper eloquently recites King’s philosophy of anti-materialism and a deep humanism that would oppose the relentless drive into a consumeristic, materialistic society that would prove antagonistic to the basic principles of dignity for all and the pursuit of a just society.

To highlight some of the text from Chapter 10: A Vision unto Death, a Truth Beyond the Grave, Pepper observes: King, he says, “inherited a dehumanized society… where all values are reduced to market values and market prices… King confronted societies’ “insatiable quest for money and material consumption.” “As the growth of corporate power parallels the increasing dominance of materialism, the movement for community control and localization becomes the natural reaction to the process of society’s dehumanization that Martin Luther King sought to reverse.”

“At the heart of the Poor People’s Campaign was the goal of empowering people in their communities to create a better life in balance with nature… and becoming part of the wooden world as zones of accountability and responsibility, which they manage themselves.”

King saw a problem in the “dominance of western materialism.” He saw the “insatiable quest for money…” and juxtaposed that with the “Poor People’s Campaign” as a “revolutionary undertaking” to counteract the pursuit of money with the pursuit of social justice.

King further challenged members of his own faith by calling Christianity “a religion of materialism” and criticizing it for undermining the world’s tribal people “across five continents, over five centuries, and enabling the Europeans to achieve world dominance of global resources.”

King scathingly denounces European culture as carrying the “materialistic torch” that “caused the deaths of hundreds of millions of people…”His critique of European culture saw it as a “materially advanced technological society running away from… Judeo-Christian heritage…” Pepper goes on to say that “the military industrial complex… [King saw it] as violating American cultural heritage by making the United States the world’s greatest purveyors of violence.””Poignantly, King prophesied that the growth of militarism would cause the end of democracy.

In King’s view, “the only alternative to disaster was to promote the perception of the oneness of humankind over the public policies of the nation.”

King aligned explicitly with Ghandi’s vision for change through civil disobedience, and he aligned with Ghandi’s humanitarian sensibility, which Pepper traces to a philosopher named John Ruskin, a critic living in the UK.

Pepper notes that by 1967, no national leader had emerged to lead the anti-war effort until MLK made his views known. As a warning to the establishment, a largely white demonstration involving 200,000 mostly middle-class protestors converged on the Pentagon, encircling it, and this presaged what would happen in Washington DC with a Poor People’s Campaign.

King was “attempting to confront the core issue of economic injustices running through American society… which included protesting the war in Vietnam and the growth of militarism.”

This “new struggle brought MLK into direct conflict with the Federal Government and its numerous agency surrogates… [serving] corporate interests.”

King’s movement, Pepper observes, was more “akin to a class revolution than an anti-colonial struggle,” and for this reason, King’s destiny was cut short by an “act of state.”

So, what are we, the readers, supposed to do with the knowledge that our government, or surrogates of our government, national security state agents, killed an American citizen endeavoring to affect a social revolution?

Well, for one, we should accept that the attack on King and others in the 1960s was a counter-revolution conducted by agents of the state; we need to accept that, in effect, historical possibilities were denied by the assassinations. Justice means reclaiming history, forcing accountability with truth commissions, and demanding reparations for the peace dividend we should have gotten.

We must then call for the same thing King did… a way to redeem King’s vision, to give King’s vision the same currency it had when he was killed, and to continue moving forward as a movement from where he left off…because since King’s assassination, things have only gotten worse in terms of our society descending into materialism and militarism. Society has degraded since King’s death. Let’s go back, figuratively speaking, and set things right.

Check out the link below for an interview with William Pepper that sheds light on the movement Dr. King was advancing in 1967: https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/WFP020403.pdf

"An Act of state"

An Act of State

The Execution of Martin Luther King

By William F. Pepper

A Book Review by Chuck Fall

William Pepper befriended Martin Luther King after King read a Ramparts Magazine article in 1967 about atrocities in the Vietnam War. Pepper’s report moved Dr. King to take a more critical stance against the war and later led him to call for a Poor People’s Movement, fusing two currents at a time of revolutionary change.

In An Act of State, William Pepper, a radical human rights lawyer, tells the story of engaging with the King family to uncover the truth around King’s murder.

MLK’s assassination was a profound shock to Pepper, which at the time drove him away from public activism to professional work, but he would return to the crime scene, almost 12 years later, on behalf of the King family to try to get James Earl Ray a new trial.

Within three days of his guilty plea, Ray claimed his innocence; Pepper’s investigation contends that Ray was set up as a scapegoat to support the state’s case of a lone gunman assassin; however, Pepper’s counter narrative contends that there was a conspiracy and it was an act of state, which describes the thesis of King’s assassination. To exonerate Ray, Pepper needed to convince a jury of an alternative explanation for what happened.

As a way to build public interest for a new trial for Ray, Pepper conducted a mock trial of the King assassination on BBC television. Though Pepper was never able to secure a new trial for Ray, who died in jail in 1998, the King family did sue Lloyd Jowers, who implicated himself as a result of the BBC TV production.

Lloyd Jowers was mentioned as a suspect, given that witnesses saw him handle a rifle reportedly used in the crime. Jowers was the landlord for the short-term room rental from which Ray is alleged to have shot King.

To deflect his role as the actual assassin, Lloyd Jowers went on ABC and told Sam Donaldson that he participated in the assassination and knew who the assassin was.

The King family sued Lloyd Jowers, and through the case, Pepper demonstrated by a preponderance of evidence that Ray did not kill King and that more plausibly it was a conspiracy of local and federal law enforcement. They won a $100.00 financial award from Jowers, and the King family was satisfied with the revelation of a conspiracy.

In Pepper’s account, there were a lot of people involved in the assassination: local mafia, local police, the FBI, and military intelligence and assassin teams that would be used as a backup if the primary assassin team of local people failed; it’s complicated.

The Plot to Kill King and Orders to Kill are two other titles by William Pepper about the King assassination that provide credible and plausible explanations for what happened and why it happened.

In a nutshell, Ray was framed and an elaborate plot was engineered; there were insiders in the Civil Rights Movement who are alleged to have aided and abetted the assassination, and there has been an ongoing cover-up that involves misinformation and assassination. Pepper reports a fascinating story of deceit and intrigue as he pieces together the bits and shards of evidence, much of it secondhand.

From his days in the 1950s and early 1960s, Pepper tells the story of King’s maturation as a social and political activist. It was a great triumph for the movement when President Johnson signed into law in 1965 the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. But King kept moving forward and wanted more reforms.

In 1967, King delivered his famous speech condemning the Vietnam War, and it was a shot across the bow for the establishment. King exhibited a willingness to branch out from civil and voting rights to more radical and contentious issues like opposing war (the military industrial complex) and opposing the systemic impoverishment of people of color. Some in the movement thought King betrayed a tacit agreement to not get too “uppity” and to not ask for too much, like ending a war.

When I think about the 1960s assassinations, including those of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Robert F. Kennedy, I wonder how history would have unfolded if these great leaders had not been killed. It is easy to imagine that the geopolitical affairs of an imperial American power would have been brought to heel under an anti-militarism policy and a pro-social justice movement. This was certainly King’s destiny.

Indeed, it is possible to imagine that if the four assassinated leaders had lived a full life, that great arc of a just history that King confidently believed was available to humankind might have unfolded.

Perhaps the highlight of An Act of State is Chapter 10, which is a discussion of King’s philosophy about change, where he was willing to go, and the implications of this for his fate. However, it should inform our current thinking about where we should be as a movement and the stance we must take to effect change: King’s vision.

Pepper eloquently recites King’s philosophy of anti-materialism and a deep humanism that would oppose the relentless drive into a consumeristic, materialistic society that would prove antagonistic to the basic principles of dignity for all and the pursuit of a just society.

To highlight some of the text from Chapter 10: A Vision unto Death, a Truth Beyond the Grave, Pepper observes: King, he says, “inherited a dehumanized society… where all values are reduced to market values and market prices… King confronted societies’ “insatiable quest for money and material consumption.” “As the growth of corporate power parallels the increasing dominance of materialism, the movement for community control and localization becomes the natural reaction to the process of society’s dehumanization that Martin Luther King sought to reverse.”

“At the heart of the Poor People’s Campaign was the goal of empowering people in their communities to create a better life in balance with nature… and becoming part of the wooden world as zones of accountability and responsibility, which they manage themselves.”

King saw a problem in the “dominance of western materialism.” He saw the “insatiable quest for money…” and juxtaposed that with the “Poor People’s Campaign” as a “revolutionary undertaking” to counteract the pursuit of money with the pursuit of social justice.

King further challenged members of his own faith by calling Christianity “a religion of materialism” and criticizing it for undermining the world’s tribal people “across five continents, over five centuries, and enabling the Europeans to achieve world dominance of global resources.”

King scathingly denounces European culture as carrying the “materialistic torch” that “caused the deaths of hundreds of millions of people…”His critique of European culture saw it as a “materially advanced technological society running away from… Judeo-Christian heritage…” Pepper goes on to say that “the military industrial complex… [King saw it] as violating American cultural heritage by making the United States the world’s greatest purveyors of violence.””Poignantly, King prophesied that the growth of militarism would cause the end of democracy.

In King’s view, “the only alternative to disaster was to promote the perception of the oneness of humankind over the public policies of the nation.”

King aligned explicitly with Ghandi’s vision for change through civil disobedience, and he aligned with Ghandi’s humanitarian sensibility, which Pepper traces to a philosopher named John Ruskin, a critic living in the UK.

Pepper notes that by 1967, no national leader had emerged to lead the anti-war effort until MLK made his views known. As a warning to the establishment, a largely white demonstration involving 200,000 mostly middle-class protestors converged on the Pentagon, encircling it, and this presaged what would happen in Washington DC with a Poor People’s Campaign.

King was “attempting to confront the core issue of economic injustices running through American society… which included protesting the war in Vietnam and the growth of militarism.”

This “new struggle brought MLK into direct conflict with the Federal Government and its numerous agency surrogates… [serving] corporate interests.”

King’s movement, Pepper observes, was more “akin to a class revolution than an anti-colonial struggle,” and for this reason, King’s destiny was cut short by an “act of state.”

So, what are we, the readers, supposed to do with the knowledge that our government, or surrogates of our government, national security state agents, killed an American citizen endeavoring to affect a social revolution?

Well, for one, we should accept that the attack on King and others in the 1960s was a counter-revolution conducted by agents of the state; we need to accept that, in effect, historical possibilities were denied by the assassinations. Justice means reclaiming history, forcing accountability with truth commissions, and demanding reparations for the peace dividend we should have gotten.

We must then call for the same thing King did… a way to redeem King’s vision, to give King’s vision the same currency it had when he was killed, and to continue moving forward as a movement from where he left off…because since King’s assassination, things have only gotten worse in terms of our society descending into materialism and militarism. Society has degraded since King’s death. Let’s go back, figuratively speaking, and set things right.

Check out the link below for an interview with William Pepper that sheds light on the movement Dr. King was advancing in 1967:

https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/WFP020403.pdf